Modernization in the kitchen

E interesant că acest interviu Bucătăria lui Stalin – A existat oare o gastronomie comunistă? a apărut mai întîi în română. După care a fost tradus şi preluat de ruşi pe mai multe situri. După care am fost invitat să vorbesc pe această temă. După care mi s-a cerut dreptul să fie publicat în 2 cărţi de limbă engleză şi am deja 2 variante de tradueri în engleză: din rusă şi din română. A mai apărut în franceză, olandeză şi lituaniană. Asta e ultima variantă englezească făcută din rusă. Se pare că bucătăria sovietică interesează, mai ales după ce a dispărut. Aia cu “philosopher” e o glumă, fireşte. E interesant că acest interviu Bucătăria lui Stalin – A existat oare o gastronomie comunistă? a apărut mai întîi în română. După care a fost tradus şi preluat de ruşi pe mai multe situri. După care am fost invitat să vorbesc pe această temă. După care mi s-a cerut dreptul să fie publicat în 2 cărţi de limbă engleză şi am deja 2 variante de tradueri în engleză: din rusă şi din română. A mai apărut în franceză, olandeză şi lituaniană. Asta e ultima variantă englezească făcută din rusă. Se pare că bucătăria sovietică interesează, mai ales după ce a dispărut. Aia cu “philosopher” e o glumă, fireşte.

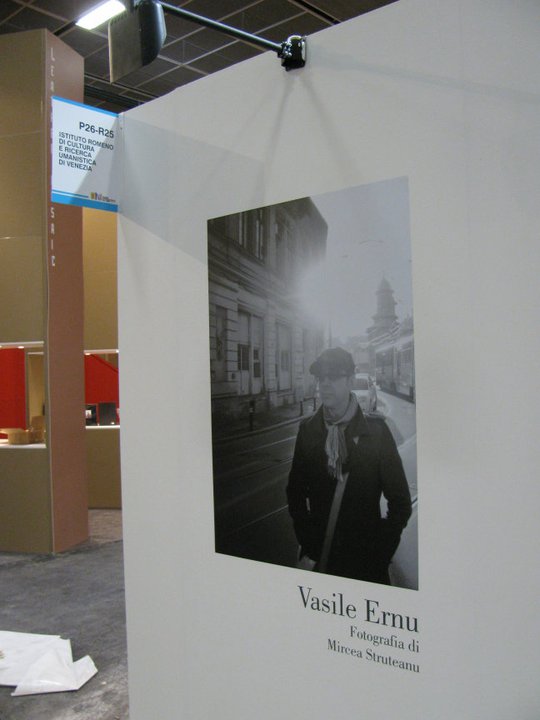

Romanian philosopher Vasile Ernu talks to the author of “Catering” Irina Glushchenko.

Translated by Olivia Stevens

Dear Irina, to begin let’s tell those who have not yet read your book what it’s about. To what extent can the subject of this book be interesting to us, who have emerged from communism 20 years ago?

It’s simplest to say that the book is about exactly what is written on the cover: catering, Mikoyan, and Soviet cuisine. But I think that discourse about that is just one of the tools by which we can try to understand the Soviet era as a whole. I love the quote from Ilf and Petrov on the “big world” and the “small world”. Here is our diet, food – this is the “small world”, the same routine, home life, which is trying to dissociate itself from the historical cataclysms. And you can begin to understand that this takes place here in this “small world”. But suddenly it turns out that through the study of the “small world” you can understand something in the “big”.

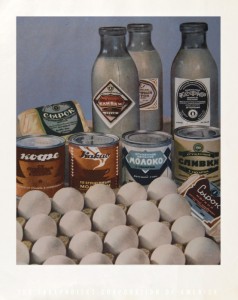

The question is whether there was sausage in the Soviet Union, related to the issue, and if it has created the Soviet people? Moreover, the more I study Soviet everyday life, the more I understand that the observation in dashes of the “small world” leads to fundamental questions such as “Why did revolution occur in Russia?”, “Was industrialization neccessary?” How did the idea come to you to write such a book? It’s a funny story. Generally, I didn’t intend to write any books. Just one beautiful day in 2002 I rode the subway and looked over a hanging advertisement for the Mikoyan Plant: pictures of sausages, the Kremlin and the inscription “Mikoyan – the official supplier of the Kremlin since 1933.” It didn’t refer to Mikoyan the person, but Mikoyan the plant, which was built in 1933 on the orders of the People’s Commissar Anastas Mikoyan for the food industry and has long been known as “Mikoyan”. I was surprised by this reference to 1933 – it was a frank appeal to Stalin’s time as a symbol of stability and prosperity. And the statement of continuity where “the Kremlin” refers to “the Kremlin” under Stalin. And who was sitting in the Kremlin in 1933? Collectivization had only just ended, and after less than a year Kirov would be killed the Great Terror would begin. I wrote an article about all of this in the newspaper «The Moscow Times», then forgot about Mikoyan and sausage. A year later one the drafters of the Texas Culinary dictionary wrote to me, she said she had read my post, was very interested in the figure of Anastas Mikoyan, and asked me to write about it. I agreed of course, but realized that I knew very little about Mikoyan. I began to read books in the library, met with his children and grandchildren, then began working in the archives. Then I went to the Mikoyan plant, read the factory newspaper of the plant… An article about the minister had long since been written, but then I discovered that the materials I had accumulated constituted a whole book. So I wrote it. From the book I understood that Mikoyan played an important role in the origin of the food industry. What exactly was this role? He created it. After all, before there hadn’t been any of the food industry in Russia as there weren’t many other industries. The creation of the food industry was part of the overall process of industrialization, which, in turn, became the main task of the Soviet state, despite the ideological rhetoric of building socialism and communism. Many people in the Soviet Union believed the system under which they lived was a socialist system. Although it is unclear why the construction of the mills is equivalent to the construction of socialism. After all, socialism – it’s still public relations. Historian Alexander Shubin, for example, calls the Soviet system “centralized industrial society with elements of the social state.” Soviet cooking reflects these aspects of social structure: the standardization of the declared equality and management from a single center. One of the key moments in the history of Mikoyan and the emergence of the Soviet food industry is related to his trip to the U.S. Reading different authors from Walter Benjamin to Ilf and Petrov (especially their travel notes “Single story America”), I have long felt this great similarity between these two systems. To what extent has the American food industry influenced the Soviet? It influenced it. Specifically in the sense that American industrialization was taken as a model. We always competed specifically with America, not India, for example, that it would be more sober. And then America in those years was considered very positively. But we must remember that “the miracles of American technology, brought forward on the Soviet soil,” according to Mikoyan, gave an amazing, unique fruit! So, as in America, it still did not succeed, but we got something of our own, unique. Mikoyan, for example, was simply shocked by American hamburgers. He suddenly saw in them just what you need to Soviet citizens, who came to the park, to the stadium – a hot meatball, placed in a bun. Tasty, affordable, and nutritious. He even purchased samples of the equipment, but hamburgers put into production in the Soviet Union were prevented by the war. But the idea of ready-made meatballs, apparently, was firmly stuck in the head of Anastas Ivanovich, and mass production of standard meatballs was still established. These, of course, weren’t hamburgers, but those famous meatballs for six kopecks, which the whole nation knows as “Mikoyan”. So our meatballs – they’re hamburgers, entirely immature! It is very interesting that Mikoyan, Ilf, and Petrov went to America about the same time. Mikoyan was fascinated by what he saw in the field of nutrition, and saw in the American food industry a huge potential for the food industry, able to serve the young Soviet state, while Ilf and Petrov were very critical and they did not like anything of what they saw in the field of nutrition. Why do their approaches vary so? They have different objectives and different views of problems. Ilf and Petrov – they are aesthetes, gourmands. They would sit in a Parisian restaurant, cut luxurious meat into small pieces and sip their red wine. But Mikoyan had a need to “feed the working man.” Feel the difference? The pace differs, and the principles are completely different. Ilf and Petrov did not like frozen food, didn’t like the “tasteless”, but a beautiful dish in the cafeteria. And for Mikoyan – it is sacred. After all, do not forget that the whole way of life in the country has radically changed. Millions of peasants became workmen. People who have fed themselves become consumers, for whom food needed to be provide. All questions needed to be solved very quickly and on an unprecedented scale. Take the same mythical sausage. Its mass production was just the result of industrialization. Earlier in the national consumption of the product didn’t exist. The shortage of sausages later arose from the fact that this product is strongly advocated, the mass consumption of sausage taught to the country, and as a result, there was not enough. One of the main themes of the book is the definition of what is called the “Soviet cuisine”. Can we talk about “Soviet cooking”? Does it really exist? This is a very important question, because if this project existed and was put into practice, then through analyzing this “project”, it may be possible to see what happened to the “new man” and the “Soviet project? It existed to the extent to which the Soviet Union and Soviet person existed. More than that, I would say that the existence of Soviet cooking is something more real and tangible than the authenticity of the first two items. Soviet cooking has survived the context of its creation. I consider the Soviet cuisine, not only in terms of recipes, not as a collection of various foods and dishes, but in terms of the so-called “consumer practices”, as culture experts love to say. And here we have an entirely unique phenomenon. Take my favorite sandwich. The word is German, but in Germany they do not understand it. In the Soviet period, there was a whole culture of the cooking and consumption of sandwiches. A thick slice of white bread, which at first is slathered with butter, then put on this a thick piece of sausage or cheese, it only exists in Soviet culture. I remember being in New York- I terribly wanted a sandwich with cheese. My American friend grabbed his head. “French cuisine? – He said. – It is very expensive. ” In the appearance of the food industry in the USSR it is interesting that in one and the same process, it joined production and consumption, individual tastes and the collective effort. Public and private spaces were intertwined in unexpected ways. The recipe was proposed as an official standard, influencing the cooking in the workers’ canteen, and in the home kitchen. Across this vast country, people began to eat the same thing. The individual kitchen becomes a factor of social integration. It merges with the ideology – and not just because the “Book of tasty and healthy foods” has quotations from Stalin and Mikoyan, but also because the recipes themselves laid down certain ideological views, a certain system of values. During one debate after my book, I was told that the Soviet cuisine could not exist, because cooking should be either national, or social. But the fact of the matter is that the Soviet Union managed to create a cuisine that was neither social nor national. It was sort of a revolution, and not only in cooking. In discussing the communist project, and specifically the “project of the USSR ” it is often found that these things are understood as different things. For some, it is an absolute evil, which comes down to the dictator, the keeping of people in concentration camps, for others – a place where they lived, where they ate “the very same” ice cream and drank “the very same” sodas, and for someone – just the battle between the two systems in which Coca-Cola won over soda, and “Snickers” was victorious over the Soviet “bar”. After reading your book, I realized that we know very little about what actually happened in the Soviet Union on the lower levels – the base of society. How do you think: the development and implementation of the “Soviet cooking” project- is it a good area for studying the integrity of the “USSR project”? Is it possible to assess any historical epoch individually? I write about the tragic duality of those times: on the one side, repression (including that in the food industry), on the other – the enthusiasm and conscious and slightly naive participation of people in the creation of a new society. The drama of the era is precisely in the combination of the exorbitant price that had to be paid for progress, and the extent of achievements, the fruits of which we still use today. Now a stereotype has formed, where it is impossible to discuss the Soviet past seriously: any attempt to peacefully reflect on that era is regarded almost as an attempt to rehabilitate totalitarianism. But at the same time we have a mountain of literature that attempts to whitewash Stalin, to prove that terrorism did not exist. But the understanding of history comes when we stop drawing cartoons of the past or engaging in its praise. With regard to “the lower levels,” I do not think that they can be identified as such outright. Historians are interested in how Stalin directed the construction of the Palace of Soviets. But they are much less interested in how soap was made in the Soviet Union. And suddenly it becomes clear that both cases were roughly the same. Stalin not only personally studied the architectural projects, but also smelled different kinds of soap. Mikoyan told about it with enthusiasm, like the sample that must be followed by a director. It turns out that in society there is no minor task. And the negligence of the director shown during the manufacture of soap may result in his death. Of course, all the traits of the industrial and mass society were not unique to the Soviet Union. Another thing is that it is in the USSR particularly that many of these traits were expressed particularly clearly and consistently, and sometimes brought to the grotesque. An essential feature of the Soviet is, of course, the presence of ideology in the various spheres of life. This does not mean that in other societies, there was no connection between ideology and way of life. But in the Soviet Union, this relationship was declared. And as a result of the discrepancies between the life and ideology were detected at every step. Let’s talk about “the bible of Soviet cuisine”, which you call “culinary orthodoxy:” The Book of healthy and delicious food. ” It played a very pertinent role, because a generation of Soviet citizens was raised on it. But on close reading you quickly realize that in the first place it is an ideological book, and only then a cookbook. What is the essence of this book, what is its function in Soviet society? First of all what strikes me is that it is a normative document. I do not accidentally call it “culinary codex” or “culinary bible”. Stalin merges all the writers’ organizations into a single Union of Writers, which should have one creative method. The same happens with the architects, painters, composers. And exactly the same way the cookbook was created. One for the whole country, for all peoples. Architects were urged to “study the heritage”, and the cookbook synthesizes the kitchen of the Soviet peoples with European cuisine, and it’s not just a synthesis. Our cooking should be the top of world cuisine, taking from all the best and uniting them for the benefit of the Soviet man. Of course, this is utopia. The real diet was very far from the ideal depicted in the book. Many of the products were simply not available in everyday life. But on the other side, they were still real. At least once in a lifetime someone saw something like that somewhere, and maybe even tried it. How was Soviet cooking introduced to the people? Was there more intense propaganda of this cooking? Well, it was introduced liked that. “The Book of Tasty and Healthy Food ” contributed more than a little. More intensive propaganda is hard to imagine. Especially when it was supported by such grandiose, graphic material! Remember those pictures -they stagger the imagination to this day. Also the fact that they portrayed a kind of IDEAL, so generally all the propaganda was based on this. The boundaries between myth and reality of Soviet life, were not only pre-arranged, but also flexible. The picture of Soviet life included what must be, what is and what will be, and all that exists simultaneously. A utopian dream is embodied in practice, and utopia becomes a reality. And from that moment it ceases to be a utopia. Utopia all the time dissolves into reality and is itself constantly evolving. Was it a dominant or alternative cuisine? What is its relationship to traditional cooking? As in the West, many have lost their everyday practice in cooking and started to buy pre-prepared products, etc. That is predominant, of course. In Soviet society in general there was something bad about alternatives. But above all, Soviet cooking swallowed Russian cooking of course. With regard to traditional cuisines, such as Caucasian, I suppose, they were very different from the Soviet. Another matter that dealt with similar products. And Soviet cooking assimilated some of the dishes of national cuisine – barbecue, soup kharcho, pasties – averaging and simplifying them to such an extent that they have lost their original connection with the traditions of national cooking. I noticed something that amazed me. Within the renovation of food industry, this popular culture with various circles (drama, music, literature, film, journalism), has developed around the factories in which workers were involved. In the study of this, what was written and put on stage, it becomes apparent that a special type of mass authentic culture was produced in addition to an element of propaganda, the grotesque and incredible kitsch. Reading the letters from readers in the original factory paper, we even see the appearance of a special type of an authentic relationship to things. People were arguing, fighting back, they had their own opinions. Today it is very difficult to understand and imagine these mechanisms, especially in countries like ours, where the state industry has almost entirely disappeared, and private industry has not appeared. How do you see and interpret the type of social, cultural and political life, which was claimed by this social class? You mean, in particular, the performance of “Abundance”, presented at the Mikoyan plant in the mid 30-ies? Oh, it’s a terrific story. Imagine this: workers will not only produce sausages, but also play them on stage, that is, immersion in the image, which Stanislavski could only dream of! In the factory newspaper a note was published from participants in a play where they tell us how to work on the role of hot dogs … And what about the text of the play in verse: “We Soviet sausages, widely infiltrated the masses…” and couplets about tea sausage and salami! So figure it out in this epoch. The soviet industry was trying to not just produce, but to some extent can shape and can even “produce” the working class. Managers are constantly working on the consciousness of the governed. The effect was twofold. On one side, communion of knowledge and culture happened. In the end, when the workers are involved in amateur theatricals, they acquire an aesthetic experience. But on the other side, everything is closely associated with the introduction of official ideology, with the formation of the people of precisely those values and habits that suit power. For example, the same performance of “Abundance”. It clearly mimics the aesthetics of the Baroque, although the workers and the words are not aware of this. The new Stalinist aesthetic was conservative, and asserted the idea of greatness of the state as a classical baroque. Taste – it’s a bourgeois idea and a relic from the standpoint of the Puritan Bolshevism, sustenance has its function and should not bring pleasure. Mikoyan appears, brought up in the Caucasus, and declares that the food should have taste. How did Mikoyan solve the issue of taste? I’m not sure he could SOLVE it. But he really wanted to. Remember, Astrid Lindgren in “Kid and Carlson”: “Why is food healthier, when it is not tasty?” Soviet dietitians were adamant. The main thing is to get the required amount of fats, proteins, carbohydrates. How they will be packed, is an uninteresting question. In addition, for some reason they thought that any spicy spices excite, food must be calm and neutral, plenty of boiled, mashed, stewed … As if for children … to Mikoyan, a Caucasian man, this was certainly distasteful. Wherever he could, he was trying to implement something tasty, spicy and expressive. He defended the title “Books of tasty and healthy food”, because originally they wanted to call it “Book of useful and healthy food.” He said: “Taste needs to be developed.” There is the same problem as with all Soviet planning. Soviet industrialization initially struggled with quantitative indicators the establishment of a mechanism responsible for quantity. But, in the words of Shubin, “coping with the quantity, the Soviet economy was losing the battle for quality.” The centralized system of Soviet industry could quickly solve simple issues. But as soon as issues become more complex, problems arose. The question of taste, which cannot be measured by formal indicators is very characteristic. What could make Mikoyan in this situation? The same thing that Stalin did – to intervene in detail and deal with personal quality control. A kind of oppressive subjectivity, which turned out to counterbalance the bureaucratic formalism. As a result, an individual subjective taste, which will take the attention of the industry, is the personal taste Mikoyan. It embodies the interest of consumers and his tastes become the tastes of millions. It affects the method through which at the highest level certain decisions were made on banal issues. I would never have believed that such a question as assortments of sausages or canning labels were discussed at the highest level. It seems an impossible scene, when Mikoyan brings to the Central Committee a few samples of soap, and Stalin with his team sniffs, probes, and even tastes the products, choosing the best option for the Soviet people. This scene – like a cross between Ilf and Petrov with Ionesco. How did they come to the decisions? Why did Stalin involve himself at the level of taste, smell and other seemingly minor details? Have the tastes of Stalin and Mikoyan become our tastes? To what level have their food preferences influenced the daily lives of several generations of Soviet citizens? An episode with soap- it’s not folklore, but cited from Mikoyan’s speeches in the 30’s. He would never have allowed himself to think about Stalin what Stalin was not. Such despotic style of leadership was accepted and welcomed in the country. The episode, which now seems grotesque and almost unbelievable, did not cause the listeners even the slightest irony. Besides that, mind you, the people didn’t believe in their own power. In fact, how you can trust the people for whom the instructions: “Do not spit on the floor in the house.” were written. Understand, if this needed to be specifically taught at the state level, it means that the majority spat and considered it totally normal. So, in talking about “Russia, which we lost,” we need to in the first place remember not the gentry and the intelligentsia in Russia, but the people who were illiterate and had to be taught elementary things … Power serves not only as a meticulous manager who does not miss a single detail, but also as an educator. And it is impossible to tell where one ends and another begins. At some point we already stopped thinking about these products or these practices someone has designed and implemented. For the next generation of Soviet people, they become natural. More than that, in the 60’s, when many of the hardships of the Stalin era were past, and a few elements of utopia realized. After all, it was understood that Stalin’s “abundance” was nothing more than a slogan. But three decades later, some features of Soviet life resembled that which for the 30’s could only be ideal. The same “Book on healthy and delicious food “, because of its huge success is related specifically to the 60’s. I once joked that the Soviet food is saved in closed structures: kindergartens, hospitals and prisons. In general, the places where people are fed daily (here sometimes added to lunch), hot meals, with lunch also consisting of three defined dishes. Well-known first, second and third: soup, meat or fish with side dish, and fruit compote. The current “catering” combines new dishes and the traditional. Like in exotic countries there is the local cuisine, and sometimes also “European”. And in our cafes: along with new dishes, without which young people already can’t imagine a diet is Soviet vinaigrette and herring “under a fur coat”. As for homemade food, it is more conservative. But in a strange way, the method of cooking, in particular for children … Mashed potatoes, broth, meatballs, porridge, – all this is a rather childish diet. In the GUM there is the so-called “57th dining room”, styled after the Soviet type. In fact, this is, of course – a kind of ideal Soviet dining room, I would say, enriched and highly embellished. The combination of the achievements of the Soviet system with capitalist abundance. It’s own kind of utopia.

|

“PR-ul trebuie păstrat în cadrul lui iniţial.” De vorbă cu scriitorul şi eseistul Vasile Ernu

Interviu realizat de Simona Barbu in PR Romania.

În Manifestul cărţii spuneaţi că “la noi se mai face încă o mare confuzie între PR, critică literară şi jurnalism cultural. E comic cum uneori, criticii literari devin PR-işti, iar PR-iştii, critici literari.” Care ar trebui să fie, în percepţia dvs. ca scriitor, profilul unui bun PR-ist cultural?

PR-ul este o tehnică, o unealtă, nu un conţinut. PR-ul lucrează cu un conţinut pe care trebuie să-l slujească. Pe mine mă deranjează cîteva lucruri în evoluţia acestei industrii. Mă enervează credinţa oarbă în PR&publicitate&marketing. Tot mai multă lume crede că e suficient să ai publicity şi deodată ai şi prosperity. Cum ironiza şi Ilf şi Petrov stilul de viaţă american: Fără publicity, n-ai prosperity. Deci PR-ul este un instrument care ajută un conţinut, nu-l subordonează. Ceea ce a devenit însă agravant e faptul că PR-ul a devenit conţinut în sine, autosuficient, mod de viaţă, formă de gîndire. Demult nu mai contează conţinuturile, ci PR-ul în sine. Adică PR&publicitate&marketing se instituie ca şi conţinut şi se impune, se vinde pe sine ca atare. PR&publicitate&marketing demult nu mai este o simplă tehnică şi un departament respectabil dar modest, ci a devenit un instrument de putere şi ideologic. Eu susţin că în acest moment PR&publicitate&marketing îndeplinesc în actualul regim funcţia pe care politrucii o îndeplineau în vechiul regim: ei sînt armata puterii, ideologii ei reali. Situaţia e chiar mai gravă: în vechiul regim politrucii erau dispreţuiţi (chiar dacă nu asumat şi pe faţă), însă acum noii politruci s-au transformat în eroi şi au impus un mod de viaţă. În ultima mea carte “Ultimii eretici ai imperiului” am scris cîteva capitole pe această temă. Nu vreau să jignesc pe nimeni, respect domeniul. Mereu dau exemplul lui Moise şi a fratelui sau Aron: Moise era un manager bun dar era catastrofal la comunicare, de aceea cu Faraonul Egiptului comunica Aarron care transmitea misajele lui Moise. Orice societate umană are nevoie de aceste instrumente. Însă ele trebuiesc cunoscute şi păstrate în cadrul lor iniţial. În momentul în care-şi depăşesc domeniul, devin nişte instrumente periculoase. Deci trebuiesc practicate cu modestie şi responsabilitate.

Consideraţi cartea cel mai ieftin şi bun instrument de educaţie. La ce nivel a ajuns, prin comparaţie cu celelalte ţări ex-comuniste, industria cărţii în România?

Industria cărţii din România s-a dezvoltat destul de mult în ultimii 10 ani. Din păcate, nu s-au dezvoltat şi alte industrii colaterale care afectează piaţa cărţii, cum ar fi de exemplu, reţelele de librării. Însă cel mai grav lucru care se întâmplă şi care afectează profund piaţa de carte pe temen mediu şi lung este dispariţia unor infrastructuri precum bibilotecile, dispariţia fondurilor de achiziţie de carte pentru bilblioteci şi mai ales degradarea sistemului de educaţie. O ţară ca România are un număr mult prea mic de cititori şi asta se datorează în primul rînd sistemului de educaţie şi al infrastructurii culturale foarte precare. Acest tip de degradare s-a întîmplat în mai toate ţările foste comuniste, însă unele din ele şi-au rezolvat parţial aceste probleme.

Care credeţi că este contribuţia blogurile de profil şi a revistelor online în mediul cultural?

Apariţia acestor surse alternative este foarte importantă, cu o singură condiţie: să nu repete aceleaşi modele ca şi cele deja existente pe print. Suportul nu rezolvă mare lucru, el este doar un instrument care te poate ajuta. Din observaţiile mele, apariţia acestor resurse a dus la dinamizarea anumitor medii culturale. Sunt bloguri şi reviste online care au început să cântarească mai mult decît clasicile reviste culturale sau cel puţin le face concurenţă serioasă. Ce e foarte important e că majoritatea se fac fără resurse finaciare şi ăsta e un factor pozitiv: scapă de dictatura profitului, a unui interes mercantil.

Are PR-ul cultural capacitatea de a transforma fenomenul culturii din apanajul unei elite într-un bun colectiv al societăţii româneşti?

Eu nu aş fetişiza prea mult PR-ul. PR-ul este un instrument, o tehnică care nu produce conţinut direct (cu toate că experienţa societăţii americane ne arată că şi un instrument ca PR-ul poate deveni conţinut). Deci PR-ul este un ambalaj a unui conţinut şi o tehnică de prezentare a acestui conţinut. Ca să poţi “PR-iza” ceva mai întîi trebuie să dispui de acest conţinut. Problema noastră este legată de producţia culturală efectivă. PR-ul ca tehnică se învaţă destul de uşor, producţia culturală este în schimb un proces care ţine de perioade lungi de timp, uneori e nevoie de generaţii ca să producă un mediu propice producţiei culturale autentice. Iar o creaţia culturală autentică conţine în sine şi un potenţial PR care e uneori mai bun ca cel învăţat în şcoală. În ce priveşte raportul cultură elitistă şi cultură de masă: cultura de mult nu mai este apanajul elitelor. Cultura demult este cultură de masă.

10 carti romanesti pentru o biblioteca de hipster

Ups, am ajuns si in topul hipsterilor. E adevarat ca din cei 10 jumatate imi sint prieteni. Textul e scris de De cristina pe Bookahoolic.

Am promis ca revenim cu un episod de inspiratie mioritica in saga hipsterismelor literare (citeste, daca ai ratat, 10 lecturi obligatorii pentru hipsteri). Si uite ca asa se intampla, nu putea lipsi o lista consistenta de titluri romanesti numai bune de plimbat in geanta eco, eventual langa un macbook de-al lui mr Jobs.

Stau si ma gandesc ce carti cool au fost de-a lungul timpului, cu ce e de bon ton sa apari in cafenea. Treaba e ca in cazul cartilor romanesti, criteriile se amesteca un pic. Iesi cu scriitorul la bere, te intalnesti cu el in club, sunteti prieteni pe Facebook.

E interesant de vazut ce face o carte cool – subiectul, editura, promovarea, prezenta autorului la evenimente urbane si mondene sau scriitura. Hm, oare de ce-oi fi lasat-o ultima? Oricum fac aceeasi mentiune pe care am facut-o si la articolul anterior: foarte multe dintre cartile astea sunt minunate, a nu se considera o critica.

Craii de Curtea Veche de Mateiu Caragiale – da, stiu ca nu va asteptati la asta, sperati intr-o tanara speranta lansata pe net. Un pic mai tarziu. Mateiu e taticul hipsterismului (si nu numai!), mereu tanar, cand toti ne visam crai si boemi, rafinati, esteti si decadenti.

Legaturi bolnavicioase de Cecilia Stefanescu – o carte curajoasa la vremea ei, care a adus pe tapet probleme tinute pana de curand sub perna. A ajutat-o mult si ecranizarea, dar si faptul ca Cecilia Stefanescu chiar scrie bine. Recomand si Intrarea Soarelui.

RealK de Dragos Bucurenci – pe vremea cand Bucurenci era scriitor si nu dansator, RealK a fost un adevarat hit literar. Publicata mai intai online, sub forma de blog, RealK a fost printre primele carti de la noi care au abordat frontal si destept problema drogurilor (tema draga hipsterimii).

Poker de Bogdan Cosa – mesaj anticorporatist, tineri, droguri, party-uri, revolta, internet – mixul perfect pentru ca o carte sa ajunga intr-o biblioteca de hipster.

Urbancolia de Dan Sociu – titlul singur spune totul. Minimalismul decadent al lui Sociu e piatra filosofala pentru hipsterul de Control. A scos recent si Pavor nocturn.

Lorgean – Jean Lorin Sterian scrie, printre multe si amestecate altele, si de lumea mondeno-urbana a Bucurestiului, cu anumite cluburi, cu anumiti oameni, cu anumite situatii. Te (Ii) recunosti. E misto.

Fuck the cool, spune-mi o poveste de Costi Rogozanu – corporatii, povesti urbane, viata noastra de zi cu zi cu advertising, bani, branduri, misticisme contemporane.

Opere – Poezii de Gellu Naum sau Zenobia– tot ceea ce nu intelegi devine interesant. Tot ceea ce e altfel te diferentiaza. Mai altfel ca Naum nici ca exista.

Bong de Alexandru Vakulovski – Vakulovski a fost mereu pe lista scurta a hipsterilor, inca de la Pizdet si Letopizdet. E foarte cool sa citesti cartile lui, pornind de la titlurile sfidatoare, pe care e tare sa le afisezi ca un statement in public, pana la limbajul de spatele blocului.

Nascut in URSS de Vasile Ernu si, mai nou, Ultimii eretici ai Imperiului. Din prima, orice hipster iti poate recita la gramaj capitolul Cum bea soldatul sovietic, din a doua ramane cu ideile anticapitaliste.

Lista ar putea continua cu cel putin de trei ori pe atat. Sunt si scriitori clasici, ajunsi cumva pe trend, sunt si scriitori contemporani, cu subiecte sexy si atitudine superioara. Ma opresc momentan. Voi ce-ati vazut prin bibliotecile hipsteresti?

Carte, cultură generală, plăcerile și utilitatea lecturii

Vasile Botnaru în dialog cu scriitorii Ion Vianu, Cristian Teodorescu și Vasile Ernu cu ocazia Zilelor Literaturii Române la Chișinău. Astăzi vom găzdui la Europa Liberă Zilele literaturii române. Trei dintre participanţii trecuţi pe afiş au putut să dea curs invitaţiei noastre de a vorbi despre literatură pe înţelesul tuturor. Adică la limita vulgarei consumaţii. Această sintagmă am găsit-o în romanul anului 2010 din România, Amor intellectualis, de Ion Vianu, care participă astăzi la masa rotundă, împreună cu Cristian Teodorescu, autorul romanului Medgidia, orasul de apoi, cel care a luat premiul Uniunii scriitorilor din România pentru anul 2009. Cel de-al treilea invitat al emisiunii este autorul cărţilor de proză Născut în URSS şi Ultimii eretici ai Imperiului, Vasile Ernu. Care mai are calitatea de iniţiator şi animator ai taifasurilor, zise Zile ale literaturii române.

Vasile Botnaru în dialog cu scriitorii Ion Vianu, Cristian Teodorescu și Vasile Ernu cu ocazia Zilelor Literaturii Române la Chișinău. Astăzi vom găzdui la Europa Liberă Zilele literaturii române. Trei dintre participanţii trecuţi pe afiş au putut să dea curs invitaţiei noastre de a vorbi despre literatură pe înţelesul tuturor. Adică la limita vulgarei consumaţii. Această sintagmă am găsit-o în romanul anului 2010 din România, Amor intellectualis, de Ion Vianu, care participă astăzi la masa rotundă, împreună cu Cristian Teodorescu, autorul romanului Medgidia, orasul de apoi, cel care a luat premiul Uniunii scriitorilor din România pentru anul 2009. Cel de-al treilea invitat al emisiunii este autorul cărţilor de proză Născut în URSS şi Ultimii eretici ai Imperiului, Vasile Ernu. Care mai are calitatea de iniţiator şi animator ai taifasurilor, zise Zile ale literaturii române.

interviul integral aici / Europa Libera

De la Torino la Chisinau

Doua saptamini foarte dificile. Doar poze va mai pot arata. Concluziile mai tirziu. Mai intii la Torino unde am lansat Nato in URSS (aici) si apoi la Chisinau unde am organizat (alaturi de ICR & Cartier) Zilele literaturii RO (aici).

Torino

Chisinau (un interviu cu Ion Vianu, Cristi Teodorescu & Ernu aici)

Zilele Literaturii Române / Ediţia a II-a

Perioada: 18–20 Mai 2011

În perioada 18-20 mai 2011 la Chişinău şi Bălţi va avea loc a doua ediţie a Zilelor Literaturii Române. Trei zile în care cititorii vor avea ocazia să se

întîlnească cu importanţi scriitori din Republica Moldova şi România. Evenimentul va cuprinde conferinţe, lecturi publice, dezbateri şi

spectacole la care vor participa: Emil Brumaru, Val Butnaru, Constantin Cheianu, Mihai Fusu, Bogdan Georgescu, Radu Pavel Gheo,

Ion Mureşan, Alina Nelega, Nicolae Popa, Arcadie Suceveanu, Maria Şleahtiţchi, Cristian Teodorescu, Ion Vianu.

Invitat special: Victor Rebengiuc.

„Este foarte important să creăm un centru de cercetare a literaturilor de tipul acesta, pentru că am constatat că există asemănări, există deosebiri şi că există un teren formidabil pentru o cercetare la nivel academic… Zilele Literaturii Române este unul dintre cele mai semnificative şi bine organizate evenimente la care am participat în ultima vreme, iar Basarabia a fost o adevărată revelaţie pentru mine.”

Eugen Negrici (participant 2010)

„Cel mai mare cîștig al primei ediții a Festivalului Zilele Literaturii Române la Chișinău este că tocmai spulberă asemenea percepții deformate și parazitare care sînt ca niște pietre în casă. Dar și instituie o urgență de a ne cunoaște mai bine și de a face lecturi critice comparate, pe perioade istorice bine delimitate. Doar după ce critici și istorici literari importanți din România se vor familiariza cu literatura scriitorilor moldoveni va dispărea și această prejudecată și tot mai mulți cititori și scriitori îi vor da dreptate lui Eugen Negrici care a avut o revelație în timpul festivalului, că unele dintre cele mai mari opere literare pe care la va da în viitor literatura română vor veni anume din Chișinău.”

Dumitru Crudu (participant 2010)

„Prin acest proiect ce reuneşte scriitori `de pe ambele maluri` ne propunem să facem un prim pas spre încetarea reproducerii ignoranţei şi necunoaşterii reciproce. La aceast eveniment vom încerca să răspundem la cîteva întrebări simple: de ce ne cunoaştem atît de puţin? Ce s-a întîmplat şi ce se întîmplă cu noi , cu poezia şi literatura noastră? Cîteva zile la rînd, importanţi scriitori de limbă română, din ambele ţări, vor citi pentru publicul larg fragmente din cărţile lor, vor discuta şi vor încerca să ofere soluţii pentru o mai bună înţelegere a fiecăruia dintre noi.”

Vasile Ernu (coordonatorul proiectului)

Program:

Miercuri, 18 Mai / Bălţi

Ora 11.00 – Conferinţă: Ion Vianu – Memorialistica văzută de un memorialist Locul: Universitatea de Stat „A. Russo“ din oraşul Bălţi,

Sala de conferinţe, bloc 1, Str. Puşkin nr. 38

Ora 14.30 – Lecturi & dezbateri: Îngeri și alcool

Invitaţi: Emil Brumaru, Ion Mureşan, Arcadie Suceveanu, Maria Șleahtițchi

Locul: Universitatea de Stat „A. Russo“ din oraşul Bălţi, Sala de

conferinţe, bloc 1, Str. Puşkin nr. 38

Moderatori: Vasile Ernu & Emilian Galaicu-Păun

Joi, 19 Mai / Chişinău

Ora 11.00 – Lectură & întîlnire: Liceele „Gh. Asachi“, „I. Creangă“

Ora 17.00 – Lectură & întîlnire: Emil Brumaru, Ion Mureşan

Locul: Librăria din Centru, Bd. Ştefan cel Mare nr. 126

Ora 19.00 – Lecturi & dezbateri: Proza nouă: spectacolul vieţii ori spectacolul textului?

Locul: Kira’s Club (Teatru „Luceafărul“), Str. Veronica Micle nr. 7

Invitaţi: Val Butnaru, Radu Pavel Gheo, Nicolae Popa, Cristian Teodorescu

Moderator: Mircea V. Ciobanu

Ora 21.00 – Teatru: Victor Rebengiuc – Legenda Marelui Inchizitor / Spectacol-lectură după Fraţii Karamazov de F. M. Dostoievski

Locul: Teatrul Municipal „Satiricus I. L. Caragiale“, Str. Mihai Eminescu nr. 55

Vineri 20 Mai / Chişinău

Ora 11.00 – Conferinţă: Ion Vianu – Povești exact așa

cum s-au întîmplat

Locul: Universitatea de Stat din Moldova, Facultatea de

Istorie şi Filosofie, blocul central, aula 511, Str. Mateevici nr. 60

Ora 17.00 – Lectură & întîlnire: Cristian Teodorescu – Medgidia, oraşul de apoi (Premiul pentru Proză al USR 2009), Ion Vianu – Amor

intellectualis (Cartea anului 2010)

Locul: Librăria din Centru, Bd. Ştefan cel Mare nr. 126

Ora 19.00 – Lecturi &dezbateri: Profesia: autor dramatic. 4 experienţe

Locul: Kira’s Club (Teatru „Luceafărul“), Str. Veronica Micle nr. 7

Invitaţi: Constantin Cheianu, Mihai Fusu, Bogdan Georgescu, Alina Nelega

Moderator: Andreea Dumitru

Ora 21.00 – Spectacol muzical: RASSM – Poezia avangardist-proletcultistă transnistreană din perioada interbelică, cu Mihai Fusu şi Dorel Burlacu (Trigon)

Locul: Kira’s Club (Teatru „Luceafărul“), Str. Veronica Micle nr. 7

Organizatori: Institutul Cultural Român, Centrul Naţional al Cărţii

Co-organizatori: Institutul Cultural Român Chişinău, Primăria Municipiului Chişinău, Editura Cartier, Librăriile Cartier, Revista Punkt

Parteneri: Teatrul Municipal „Satiricus I. L. Caragiale“, Facultatea de Istorie şi Filosofie a Universităţii de Stat din Moldova, Universitatea de Stat „A. Russo“ din oraşul Bălţi, Centrul de Studiere al Totalitarismului, Kira’s Club

Parteneri media: Contrafort, Radio Europa Liberă, Ziarul de Gardă, Jurnalul de Chişinău, Timpul, Unimedia

Coordonator proiect: Vasile Ernu / Date contact: 0693 80512 (MD), 0723 913 486 (RO) / v_ernu@yahoo.com

Nato in URSS la tirgul de carte de la Torino

Nato in URSS (ed. Hacca) va fi lansat la Tirgul de carte de la Torino.

Joi 12 mai /Sala Blu

Ora 20:30

Invitati: Vasile Ernu, Anita N.Bernacchia, Stefano Galierani, Paola Zoppi, Caterina Morgantini

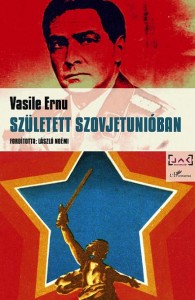

Nascut in URSS de Vasile Ernu a fost publicat in limba maghiara

Volumul Născut în URSS de Vasile Ernu a apărut în limba maghiară, la editura L’Harmattan, în traducerea lui László Noémi, cu titlul Született Szovjetunióban.

Volumul Născut în URSS de Vasile Ernu a apărut în limba maghiară, la editura L’Harmattan, în traducerea lui László Noémi, cu titlul Született Szovjetunióban.

Născut în URSS reprezintă debutul lui Vasile Ernu (Polirom, 2006, ediţia a II-a în 2007, ediţia III-a în 2010). Volumul a fost distins cu Premiul pentru debut al României literare şi cu Premiul pentru debut al Uniunii Scriitorilor din România. Nominalizări: Premiul de debut al revistei Cuvîntul, Premiul pentru Roman şi Memorialistică al revistei Observator cultural şi Premiul Opera Prima al Fundaţiei Anonimul.

Volumul a mai apărut recent la editura Akal din Spania, cu titlul Nacido en la URSS (traducere de Corina Tulbure), dar si la editura Hacca din Italia, in traducerea Annitei Bernacchia, cu titlul Nato in URSS.

De asemenea, Născut în URSS a mai apărut în anul 2007 la editura Ad Marginem din Rusia (traducere de Oleg Panfil) şi în 2009 la editura KX – Critique & Humanism din Bulgaria (traducere de Stilyan Deyanov).

Cartea este în curs de apariţie la editura Claroscuro din Polonia şi la editura Sulakauri din Georgia.

„Vasile Ernu e tare prin relaxarea şi forţa cu care uneşte şi simetrizează Literatura şi Mesajul.” (Mihai Iovănel)

„Cel mai spectaculos debut al ultimilor ani este, de departe, cel al lui Vasile Ernu.” (Bianca Burţa-Cernat)

„Vasile Ernu îşi permite luxul „iresponsabilităţii”, lux extrem de costisitor într-o cultură de provincie. Îşi permite formularea unei întrebări cu argumentaţie simplă care să neliniştească profund. Zguduirea adevărului „de la sine înţeles” într-un ritm nonşalant, aproape prietenos – aceasta e finalitatea, fără dorinţă emfatică de rezolvare a aporiei. Ernu împrumută aroganţa imperiului uresesist pierdut în istoria sa personală şi o foloseşte exact în sensul contrar pe care-l puseseră la cale propagandiştii războiului rece.” (Costi Rogozanu)

„L-am citit pe Ernu. Acest autor trebuie găsit cu orice preţ şi citit, citit, citit: Must Read! Scrie fără utopism şi ideologii şi mai ales fără ură. Scrie pur şi simplu bine, cu o frumoasă limbă simplă, ironică şi lirică.” (Gherman Sadulaev)

Vasile Ernu este născut în URSS în 1971. Este absolvent al Facultăţii de Filosofie (Universitatea „Al.I.Cuza”, Iaşi, 1996) şi al masterului de Filosofie (Universitatea Babeş-Bolyai, Cluj, 1997). A fost redactor fondator al revistei Philosophy&Stuff şi redactor asociat al revistei Idea artă+societate.

A activat în cadrul Fundaţiei Idea şi Tranzit şi al editurilor Idea şi Polirom. În ultimii ani a ţinut rubrici de opinie în România Liberă şi HotNews, precum şi rubrici permanente la revistele Noua Literatură, Suplimentul de Cultură şi Observator Cultural.

În 2009 publică la editura Polirom volumul Ultimii eretici ai Imperiului, în curs de apariţie la Editura Ad Marginem din Rusia şi la editura Hacca din Italia. Volumul a vost nominalizat la Premiul pentru Eseu al revistei Observator cultural (2009)şi a primit Premiul Tiuk! 2009.

Back in the USSR

Massimiliano Di Pasquale / Legnostortosabato / 16 aprile 2011

«Il rischio di parlare della vita quotidiana di un’epoca trascorsa comporta, senza volerlo una certa dose di nostalgia. In primo luogo, però, come concetto, la nostalgia è in diretta contraddizione con l’ homo sovieticus, per il semplice motivo che è un’utopia rivolta al passato, mentre lui crea utopie rivolte al futuro. In secondo luogo, la nostalgia, come forma di ritorno a casa è impossibile, poiché per noi homines sovietici non esiste più una casa».

«Il rischio di parlare della vita quotidiana di un’epoca trascorsa comporta, senza volerlo una certa dose di nostalgia. In primo luogo, però, come concetto, la nostalgia è in diretta contraddizione con l’ homo sovieticus, per il semplice motivo che è un’utopia rivolta al passato, mentre lui crea utopie rivolte al futuro. In secondo luogo, la nostalgia, come forma di ritorno a casa è impossibile, poiché per noi homines sovietici non esiste più una casa».

Vasile Ernu, scrittore e filosofo romeno nato in Bessarabia, regione compresa tra i fiumi Prut e Dnistr, attualmente suddivisa tra Moldova e Ucraina, è consapevole che narrare un mondo scomparso è impresa complessa e rischiosa.

Il rischio di uno sguardo offuscato dal sentimento della nostalgia (etimologicamente: il desiderio melanconico e violento di tornare in patria, ossia di rivedere i luoghi dove passammo l’infanzia e dove albergano oggetti cari, il quale è cagione di profonda tristezza e di tale sconcerto nell’economia animale, da produrre persino la morte) incombe da sempre, come una Spada di Damocle, su tutti coloro che decidono di raccontare, attraverso la letteratura, un’entità statuale o geopolitica che la Storia ha dissolto.

La sfida affrontata da Ernu in Nato in Urss, romanzo già vincitore del premio dell’Unione degli Scrittori Romeni per il debutto, uscito in Italia recentemente per i tipi della Hacca, è la stessa che riguardò a suo tempo scrittori del Finis Austriae come Roth e Von Rezzori che attraverso pagine di rara bellezza e sì, talvolta anche profondamente nostalgiche, rievocarono l’Impero asburgico.

L’autore romeno nella prefazione sembra particolarmente preoccupato dall’idea che un sentimento nostalgico possa inficiare la validità del suo libro.

Uso la parola libro piuttosto che romanzo perché a ben vedere Nato in Urss è una sorta di abbecedario del mondo sovietico. Ed è proprio la natura di abbecedario a renderlo estremamente interessante e al contempo potenzialmente oggetto di fraintendimento.

Ciò che sembra assillare Ernu è l’idea da un lato di fornire un ritratto eccessivamente benevolo di un mondo che è imploso per le sue profonde contraddizioni politico-sociali ed economiche, dunque sconfitto dalla Storia, dall’altro quello di portare acqua al mulino di tutti coloro che sono stati gli avversari di quel modello di società totalitaria.

«Guardando indietro, mi rendo conto che, una volta scomparsa l’Unione sovietica e il comunismo, qualcosa è andato perduto. Non saprei dirvi cosa. […] Non sono in grado di identificare con precisione la perdita, ma ne vivo tutta la tristezza».

E poi ancora: «Ritengo, con buona convinzione, che sia stato perso qualcosa di essenziale e significativo nella nostra esperienza umana. Ma questa perdita non può essere né sostituita, né riabilitata. Con un po’ di buona volontà, ritengo che una perdita del genere possa essere sola compresa».

Le pagine migliori di un lavoro riuscito, piacevole da leggere, sono quelle in cui Ernu fa prevalere la sua veste di narratore puro, dotato di una prosa brillante e ironica.

I 53 capitoletti che compongono quest’opera appaiono dunque simili ai tasselli di un puzzle che, una volta ricomposto, ci fornisce un’immagine non dico onnicomprensiva, ma sicuramente dettagliata dell’universo sovietico attraverso l’epica dei cosmonauti, il rock-jazz degli Stiliagy, i racconti sulla distillazione domestica di vodka, samogon e quant’altro («costruire il comunismo senza alcool è come fare il capitalismo senza pubblicità»), o il sesso all’interno delle komunalky (gli spazi abitativi in comune dove sotto lo stesso tetto alloggiavano più famiglie).

Meno convincenti invece i passi in cui Ernu, vestiti inconsciamente (?) i panni del comunista nostalgico, dimentica il registro ironico da narratore puro e indulge forse un po’ troppo verso la scintilla utopica di Lenin.

«Ripetere Lenin significa accettare che “Lenin è morto”, che la soluzione specifica da lui indicata ha fallito, anche in modo mostruoso, ma che dentro c’era una scintilla utopica che vale la pena di tenere accesa. Ripetere Lenin significa individuare la differenza tra quel che Lenin ha fatto realmente e il nuovo orizzonte che ha aperto. Non vuole dire ripetere ciò che Lenin ha fatto, ma ripetere i suoi tentativi mancanti, le sue possibilità perdute».

Vasile Ernu – Nato in Urss – Hacca Editore (2010) € 14,00, 328 pagg. Traduttore Bernacchia A. N.

„Poehali!”

Pe 12 aprilie, acum 50 de ani, primul om părăsea planeta Pămînt pentru a cuceri Cosmosul. Iuri Gagarin care avea să devină simbolul unei „generaţii a decolării”, „generaţia Sputnik”, a înfăptuit zborul la care omenirea visase multe milenii. Zilele acestea am intrat în dialog cu trei cunoscuţi intelectuali ruşi: filosoful Alexandr Ivanov, criticul literar Lev Danilkin, autorul unei cărţi despre Gagarin şi scriitorul (dar şi un excelent traducător din limba română) Oleg Panfil. Tema discuţiei noastre este semnificaţia şi actualitatea „fenomenului Gagarin” şi al „generaţiei Sputnik”. Am ţinut să aduc în discuţie acest subiect important mai ales văzînd că marea parte a presei româneşti are o singură întrebare la acest capitol: a băut sau nu a băut Gagarin? Transformarea subiectelor semnificative în scandal ieftin şi barbarie glamour devine insuportabilă. Problema majoră e ca glamourul se dizolvă treptat şi rămîne numai barbaria.

Sîntem în legătură directă cu Ivanov (Moscova), Danilkin (Bilbao), Panfil (Chişinău). Deci, cum ar spune Gagarin: „Poehali!” [„Să mergem!”]… (traducerea o asigură: Igor Mocanu)

Integral puteti citi pe CriticAtac…

si Underwood cu Gagarin, cit te-am iubit… o fresca a epocii